Speech Evolution and the Origin of Language — or Why Humans are Awesome

How did we, as humans, come to dominate the earth? I fundamentally believe that the core reason our species is top dog, so to speak, is our ability to communicate complex thought processes with one another very efficiently. We are not the fastest species on earth; we are certainly not the strongest; and the pets we have in our homes generally have more acute senses than we do. Yet we have this ability, unique in nature, to speak. This has allowed us to master the art of cooperation and in turn, to exploit natural economies of scale. From an evolutionary standpoint, these complementary skills for communication — one a cognitive skill (language) and the other a motor skill (speech) — are a tour-de-force of coordinated systems. Speech evolution and the origin of language may not be something you think about everyday, but read on to understand why you are even more awesome than you realized.

Speaking and swallowing … pick one.

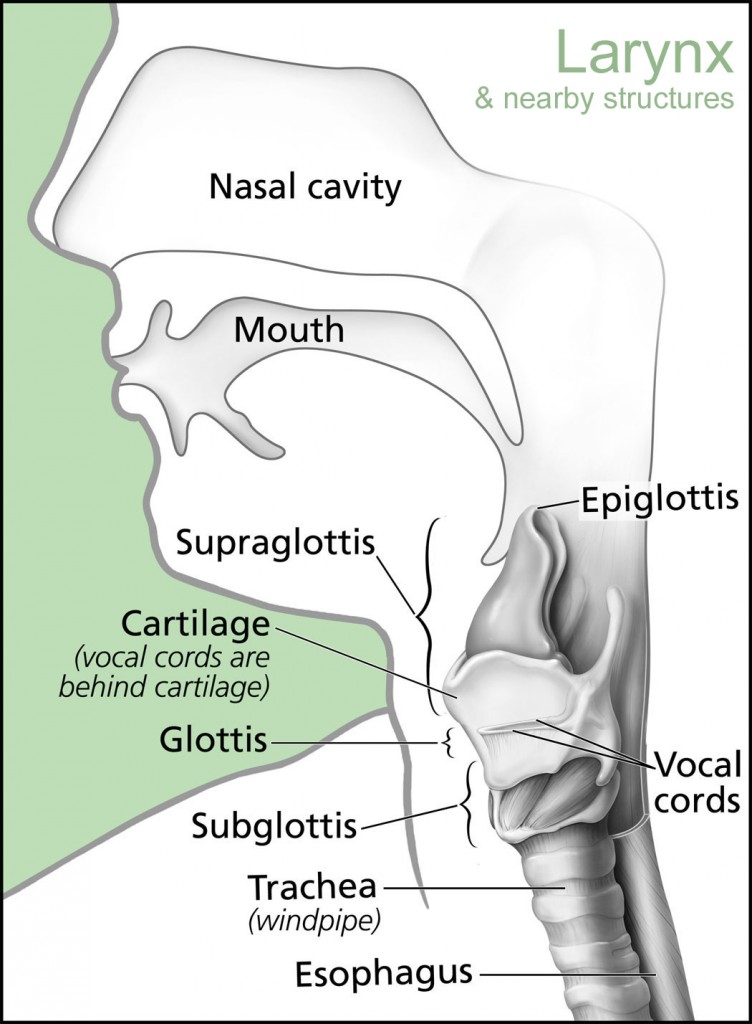

One of the first things a study of the anatomy and physiology of speech will teach you is that the human swallowing system is incredibly flawed and fragile, compared to that of other animals. What relevance does swallowing have to a discussion on speech, you might ask? Well, at some point in our evolution, the human species “decided” that an L-shaped oropharynx (i.e. mouth and throat) was preferable because it gave us the resonating cavity necessary to produce the huge range of crazy vowel and consonant sounds in our languages. We basically needed our larynx, which houses the vocal cords, to be very low down, compared to other animals, so that when sounds are produced by the vocal cords, there is a lot of room for us to be able to shape those sounds. Other animals’ larynxes are much closer to their mouths, so they’re unable to shape the sounds made by their vocal cords in the same ways that we can.

One of the first things a study of the anatomy and physiology of speech will teach you is that the human swallowing system is incredibly flawed and fragile, compared to that of other animals. What relevance does swallowing have to a discussion on speech, you might ask? Well, at some point in our evolution, the human species “decided” that an L-shaped oropharynx (i.e. mouth and throat) was preferable because it gave us the resonating cavity necessary to produce the huge range of crazy vowel and consonant sounds in our languages. We basically needed our larynx, which houses the vocal cords, to be very low down, compared to other animals, so that when sounds are produced by the vocal cords, there is a lot of room for us to be able to shape those sounds. Other animals’ larynxes are much closer to their mouths, so they’re unable to shape the sounds made by their vocal cords in the same ways that we can.

Have a look at the illustration to see how low the larynx is in humans. You’ll also notice that right below the vocal cords is the trachea (or wind pipe) which leads directly to the lungs. At all costs, we need to keep the lungs free of anything other than air. The problem is that gravity is an inescapable force and the only thing keeping food out of our lungs and a possibly deadly pneumonia, is a flap of tissue called the epiglottis. If the epiglottis is not correctly engaged during swallowing, food or liquid could get in the lungs. In neurological diseases such a Parkinson Disease or stroke, the human swallowing mechanism is especially vulnerable and a whole subset of speech pathologists deals with treating disorders of swallowing. But, animals with the larynx much closer to the mouth don’t have this problem.

So, we made an evolutionary trade-off: we developed speech, conquered the world, but have this Achilles’ heel in our swallowing function. Life really is a series of trade-offs.

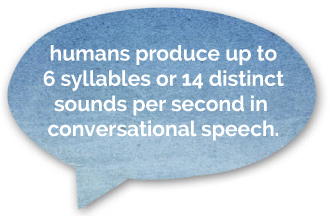

We’re all Olympic Speakers

You also probably didn’t know that speech is the single most complex thing we do with our bodies on a daily basis, from a standpoint of movement. Humans can produce up to 6 syllables or 14 distinct sounds per second in running, conversational speech. As you read this, please take a moment to reread the first two seconds of this paragraph and focus intently on the dazzlingly complex “dance” you are undertaking. This dance doesn’t include just your tongue — the primary articulator of speech; it includes the lips, the soft palate, the vocal cords and even the lungs. Knowing all this, it shouldn’t be surprising that approximately 7.5% of children have difficulty coordinating this dance and exhibit a clinically significant speech sound disorder. These coordinated speech movements are so complex that it would be seemingly impossible for young children to consciously and piece-by-piece learn how to speak; this amazing skill we are endowed with has to be something we are simply born with, or hardwired to do. This idea is one of the main contributions of perhaps the most famous and influential figure in the field of linguistics, MIT professor Noam Chomsky. His breakthroughs have led linguists to search for a universal grammar, or an underlying structure of language that is common to us all.

You also probably didn’t know that speech is the single most complex thing we do with our bodies on a daily basis, from a standpoint of movement. Humans can produce up to 6 syllables or 14 distinct sounds per second in running, conversational speech. As you read this, please take a moment to reread the first two seconds of this paragraph and focus intently on the dazzlingly complex “dance” you are undertaking. This dance doesn’t include just your tongue — the primary articulator of speech; it includes the lips, the soft palate, the vocal cords and even the lungs. Knowing all this, it shouldn’t be surprising that approximately 7.5% of children have difficulty coordinating this dance and exhibit a clinically significant speech sound disorder. These coordinated speech movements are so complex that it would be seemingly impossible for young children to consciously and piece-by-piece learn how to speak; this amazing skill we are endowed with has to be something we are simply born with, or hardwired to do. This idea is one of the main contributions of perhaps the most famous and influential figure in the field of linguistics, MIT professor Noam Chomsky. His breakthroughs have led linguists to search for a universal grammar, or an underlying structure of language that is common to us all.

How we Really learn language

So, if speech and language are innate in humans, shouldn’t babies be a “blank slate”? In other words, shouldn’t a baby born to Thai parents in Sweden be able to learn to make the very different sounds found in both Thai and Swedish? Yes! In fact, babies as young as 6 months of age are able to distinguish two different speech sounds that adults, or even ten-year olds cannot. Take the English /p/ sound. We actually say it in two slightly different ways. At the beginning of words we say the /p/ sound with an extra burst of air. Put your hand in front of your mouth as you say “pig” and you’ll feel this burst or puff of air. But, when we say /p/ in the middle of the word, as in “happy” we don’t emit this extra burst of air. But, burst or no burst of air, a /p/ is still a /p/ in English. However, this extra burst of air, or aspiration as linguists call it, can change the meaning of the word in other languages, such as many of the languages of the northern and central parts of the Indian Subcontinent, such as Hindi and Bengali. For example, “pal” in Hindi means “take care of” but “phal” (the superscript “h” denotes this burst of air) means “knife blade”. The average six-month old baby exposed to English as a language environment can hear this distinction in speech, but by the time that baby is seven years old, /p/ just sounds like a /p/.

English is Easy?! Think again

Multiple-language learning is a “use it or lose it” proposition, so many people do not realize the dazzling diversity of the sounds of the world’s language. But before you assume the sounds of English are common and boring, take our /th/ sound — as in “the” or “think”). This sound is quite rare in the world and, if you’ve ever heard someone new to English try to say this sound, not an easy one to say either. In fact, of the world’s major languages, only Arabic, Greek and Catalan Spanish have either of these sounds. Also, our North American English /r/ is comparatively rare, and as I can attest from my professional work, can be very challenging to learn.

Listen to this sample of some crazy sounds of the world’s languages. You can click on each symbol to hear how it is correctly produced. Don’t worry too much about what all the terms mean – there is a dizzying array of jargon words in the field of linguistics! – just enjoy the amazing variety of sounds we are able to make. Of particular note are the clicks sounds found mostly in the San languages of South Africa, Namibia and Botswana, and the so-called ejectives, which are found in the many exceedingly difficult and exotic languages of the Caucasus mountains of southern Russia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. For some extra nerdiness, check out this video of the most basic of a language’s words, its numbers, from the Adyghe or Circassian language of the northwest Caucasus mountains. You can really hear how distinct these Caucasian languages are — coincidentally, the words for “two” and “twenty” do sound quite similar to that of English.

Listen to this sample of some crazy sounds of the world’s languages. You can click on each symbol to hear how it is correctly produced. Don’t worry too much about what all the terms mean – there is a dizzying array of jargon words in the field of linguistics! – just enjoy the amazing variety of sounds we are able to make. Of particular note are the clicks sounds found mostly in the San languages of South Africa, Namibia and Botswana, and the so-called ejectives, which are found in the many exceedingly difficult and exotic languages of the Caucasus mountains of southern Russia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. For some extra nerdiness, check out this video of the most basic of a language’s words, its numbers, from the Adyghe or Circassian language of the northwest Caucasus mountains. You can really hear how distinct these Caucasian languages are — coincidentally, the words for “two” and “twenty” do sound quite similar to that of English.

With Language, context is everything

Wondering about English’s weird spelling conventions? Why does a word spelled “through” sound the way it actually does in running speech? Because, many centuries in the past, English had a velar fricative (see the link to the chart above), sounding like a guttural “ch” as in the Scottish word “loch”. Over time, people stopped saying this last guttural sound and eventually the sound dropped out of modern English altogether. Yet, the sound remains in our written language, which changes a lot more slowly. No one truly knows how our languages will change. Unfortunately, many of the world’s less widely spoken languages are becoming extinct, taken over by our own infectious English and other culturally dominant languages like Spanish and Russian.

Finally, remember that like the people who use language, language itself is a living organism and is always changing. So, when your father or grandmother corrects you because you said, “honey, I shrunk the kids” and not “honey, I shrank the kids,” you can retort something like the following:

while “shrank” has historically been the dominant way to conjugate the simple past tense of the verb “to shrink” in English, if enough people begin to say “shrunk” then eventually it won’t sound wrong to a critical mass of speakers of English. And “shrunk” will become the “correct” way of converting “shrink” into the simple past tense.

Perhaps for this word, the transition has already happened.

Speech and Language truly are magic. Even though “magic” is something of a hackneyed term to describe something you’re constantly amazed by, I simply can’t think of any more appropriate word for this complex mechanism of communication that we employ so effortlessly. No matter how many different means of communication have been invented since the advent of the internet, there will likely never be anything nearly as efficient and effective as speech in conveying our thoughts. Learning correct speech is a formidable challenge, and after all, may well be more complex than rocket science!